It's hard to describe in a few words how awesome it was and how much we and our portfolio founders have been able to learn thanks to all the amazing speakers who were willing to share their insights at the event. I'll try to follow-up with some additional notes later, but for now here are some visual impressions from the meetup:

Impressions from the PNC SaaS Founder Meetup 2014 from Point Nine Capital

Huge thanks to all attendees and a special thanks to all of our incredible speakers and panelists:

Aaron Ross (Author of "Predictable Revenue"; former Director of Corporate Sales, Salesforce.com)

Albert Wenger (GP, Union Square Ventures)

Bill Macaitis (Former CMO, Zendesk; former SVP Online Marketing, Salesforce.com)

Boris Wertz (GP, Version One Ventures)

Colin Bramm (Founder & CEO, Showbie)

David Bizer (Founder, Talent Fountain; former Staffing Manager, Google)

David Hassell (Founder & CEO, 15Five)

Donna Wells (President & CEO, Mindflash; former CMO, Mint)

Doug Camplejohn (Founder & CEO, Fliptop)

Everett Oliven (National VP Sales, SAP)

Gil Penchina (serial entrepreneur & angel investor)

Heiko Schwarz (Founder & MD, riskmethods)

Hiten Shah (Founder & CEO, KISSmetrics)

Jason M. Lemkin (Managing Director, Storm Ventures; former Founder & CEO, EchoSign)

Jean-Christophe Taunay-Bucalo (Chief Revenue Officer, Vend)

Joel York (Founder & CEO, Markodojo; former CMO, Meltwater Group)

Julien Lemoine (Founder & CTO, Algolia)

Lars Dalgaard (GP, Andreessen Horowitz; former Founder & CEO of SuccessFactors)

Lincoln Murphy (Customer Success Evangelist, Gainsight)

Mark MacLeod (CFO, FreshBooks; former GP, Real Ventures)

Matthew Romaine (Founder & CTO, Gengo)

Nick Franklin (former MD Asia, Zendesk)

Nick Mehta (CEO, Gainsight)

Nicolas Dessaigne (Founder & CEO, Algolia)

Nikos Moraitakis (Founder & CEO, Workable)

Omer Gotlieb (Founder & Chief Customer Officer, Totango)

Paul Joyce (Founder & CEO, Geckoboard)

Rian Gauvreau (Founder & COO, Clio)

Ryan Engley (Director of Customer Success, Unbounce)

Ryan Fyfe (Founder & CEO, ShiftPlanning/Humanity)

Sean Ellis (Founder & CEO, Qualaroo)

Sean Jacobsohn (Principal, Norwest Venture Partners)

Sharad Mohan (Chief Customer Officer, Vend)

Steven Silberbach (VP Global Sales, Clio; former Area VP Sales, Salesforce.com)

Todd Varland (Solutions Architect)

Tomasz Tunguz (Partner, Redpoint Ventures)

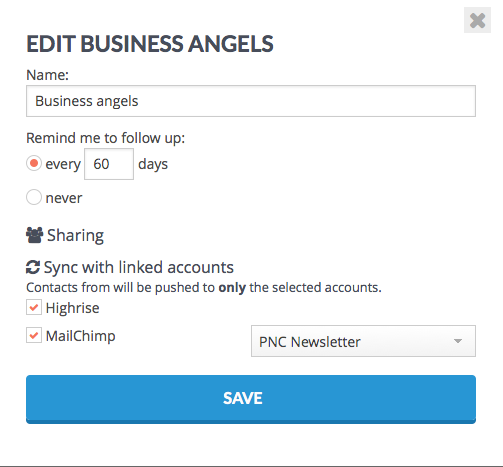

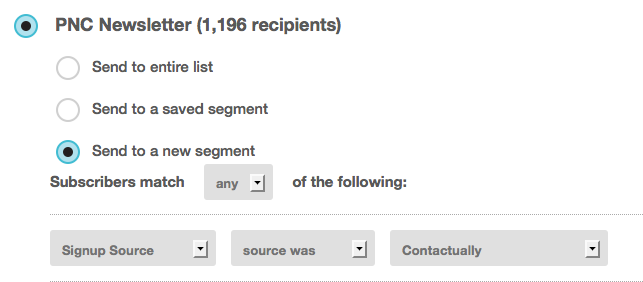

Zvi Band (Founder & CEO, Contactually)

Huge thanks to all attendees and a special thanks to all of our incredible speakers and panelists:

Aaron Ross (Author of "Predictable Revenue"; former Director of Corporate Sales, Salesforce.com)

Albert Wenger (GP, Union Square Ventures)

Bill Macaitis (Former CMO, Zendesk; former SVP Online Marketing, Salesforce.com)

Boris Wertz (GP, Version One Ventures)

Colin Bramm (Founder & CEO, Showbie)

David Bizer (Founder, Talent Fountain; former Staffing Manager, Google)

David Hassell (Founder & CEO, 15Five)

Donna Wells (President & CEO, Mindflash; former CMO, Mint)

Doug Camplejohn (Founder & CEO, Fliptop)

Everett Oliven (National VP Sales, SAP)

Gil Penchina (serial entrepreneur & angel investor)

Heiko Schwarz (Founder & MD, riskmethods)

Hiten Shah (Founder & CEO, KISSmetrics)

Jason M. Lemkin (Managing Director, Storm Ventures; former Founder & CEO, EchoSign)

Jean-Christophe Taunay-Bucalo (Chief Revenue Officer, Vend)

Joel York (Founder & CEO, Markodojo; former CMO, Meltwater Group)

Julien Lemoine (Founder & CTO, Algolia)

Lars Dalgaard (GP, Andreessen Horowitz; former Founder & CEO of SuccessFactors)

Lincoln Murphy (Customer Success Evangelist, Gainsight)

Mark MacLeod (CFO, FreshBooks; former GP, Real Ventures)

Matthew Romaine (Founder & CTO, Gengo)

Nick Franklin (former MD Asia, Zendesk)

Nick Mehta (CEO, Gainsight)

Nicolas Dessaigne (Founder & CEO, Algolia)

Nikos Moraitakis (Founder & CEO, Workable)

Omer Gotlieb (Founder & Chief Customer Officer, Totango)

Paul Joyce (Founder & CEO, Geckoboard)

Rian Gauvreau (Founder & COO, Clio)

Ryan Engley (Director of Customer Success, Unbounce)

Ryan Fyfe (Founder & CEO, ShiftPlanning/Humanity)

Sean Ellis (Founder & CEO, Qualaroo)

Sean Jacobsohn (Principal, Norwest Venture Partners)

Sharad Mohan (Chief Customer Officer, Vend)

Steven Silberbach (VP Global Sales, Clio; former Area VP Sales, Salesforce.com)

Todd Varland (Solutions Architect)

Tomasz Tunguz (Partner, Redpoint Ventures)

Zvi Band (Founder & CEO, Contactually)