Note: This article first appeared as a guest post on the popular KISSmetrics blog. Thanks to Hiten Shah and Sean Work at KISSmetrics for publishing it. I'm republishing the post here as a series of two shorter posts, with a few small edits.

Anyone who has ever worked in marketing or advertising has heard the

quote, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I

don’t know which half.” It is from John Wanamaker and dates back to the 19th century.

Fortunately, the industry has come a long way since then, and especially in the last 10 to 20 years, new technologies have made

advertising more measurable than ever. However, there’s still a

considerable gap between what people could measure and what they actually are measuring, and that leads to significant under-optimization of advertising and marketing dollars.

In B2B SaaS, which we at Point Nine Capital focus a lot of our efforts on, there are two techniques that I feel are particularly important but not used widely enough – cohort analysis and multi-touch attribution analysis. In this series of posts, I’ll try to provide a brief introduction to both methodologies and explain why I think they are so important.

A Quick Primer about Cohort Analysis

If you're a reader of this blog or know me a bit, you know that I'm a huge fan of cohort analysis and have written about the topic before. If you’re new to the topic, a cohort analysis can be broadly defined

as a dissection of the activities of a group of people (such as users or customers), who share a common characteristic, over time. In SaaS, the most frequently used common characteristic for grouping

customers is “join date”; that is, people who signed up or became paying

customers in the same period of time (such as a month).

Let’s look at an example, and it will become much clearer:

In this cohort analysis, each row represents all signups that

converted to become paying customers in a given month. Each column

represents a month in your customer’s life. The cells show the

percentage of retained customers of the respective cohort in the

respective “lifetime month.”

So What?

Why is it so important to do a cohort analysis when looking at usage

metrics or retention and churn? The answer is that if you look at only

the overall numbers, such as your overall churn in a calendar month, the

number will be a blend of the churn rate of older and newer customers, which can lead to erroneous conclusions.

For example, let’s consider a SaaS business with very high churn in

the first few lifetime months and much lower churn from older customers – not unusual in SaaS. If the company starts to grow faster, the

blended churn rate will go up, simply because the percentage of newer

customers out of all customers will grow. So, if they look at only the

blended churn rate, they might start to panic. They would have to do a

cohort analysis to see what’s really going on.

What else can you see in a cohort analysis? Whatever the key metrics

are in your particular business, a cohort analysis lets you see how

those metrics develop over the customer lifetime as well as over what

might be called product lifetime:

If you read the chart above (which I've borrowed from my colleague Nicolas) horizontally, you can see how

your retention develops over the customer lifetime, presumably something

that you can link to the quality of your product, operations, and

customer support. Reading it vertically shows you the retention

at a given lifetime month for different customer cohorts. This might be

called product lifetime, an, especially if you look at early lifetime

months, it can be linked to the quality of your onboarding experience

and the performance of your customer success team.

The Holy Grail of SaaS!

Maybe most importantly, a cohort analysis is the best way to estimate CLT (customer lifetime) and CLTV (customer lifetime value),

which informs your decision on how much you can spend to acquire a new

customer. As mentioned above, churn usually isn’t distributed linearly

over the customer lifetime, so calculating it based on the blended churn

rate of the last month doesn’t give you the best estimate. A better way

is shown in the second tab of this spreadsheet, where I calculated/estimated the CLT of different cohorts.

A cohort analysis is even more essential when it comes to CLTV.

Looking at how revenues of customer cohorts develop over time lets you

see the impact of churn, downgrades/contractions, and

upgrades/expansions:

This chart shows a cohort analysis of MRR (monthly recurring revenue)

of a fictional SaaS business. As you can see in the green cells, it’s a

happy fictional SaaS business as it has recently started to enjoy negative churn, which many regard as the holy grail in SaaS.

Still not convinced that you need cohort analyses to understand your SaaS business? :-) Let me know in the comments.

Thoughts on Internet startups, SaaS and early-stage investing from Christoph Janz @ Point Nine Capital.

Wednesday, June 04, 2014

Thursday, May 15, 2014

It's a ZEN day!

Today is a very special day for me as as an entrepreneur and investor. About an hour ago, Zendesk went public on the New York Stock Exchange. The last time I watched an IPO so carefully was when Shopping.com, the company that had bought my price comparison startup, went public – almost ten years ago.

Here are a few visual impressions of my love affair with Zendesk, which began six years ago:

Huge congrats and thanks to the entire Zendesk team – I couldn't be more proud of you guys!

Here are a few visual impressions of my love affair with Zendesk, which began six years ago:

Huge congrats and thanks to the entire Zendesk team – I couldn't be more proud of you guys!

Wednesday, May 07, 2014

Three more ways to look at cohort data

I've just added three new charts to my Excel template for cohort analysis.

The second chart is based on exactly the same data but shows MRR for calendar months as opposed to cohort lifetime months, and it uses a slightly different visualization:

The third chart shows cumulated revenues minus CACs for different customer cohorts, i.e. it shows how much revenues a customer cohort has generated less the costs that it took to acquire the cohort:

What you can see here is that the first cohorts cross the x-axis (a.k.a. become profitable) around the 6th lifetime month, whereas newer cohorts are crossing or can be expected to cross the x-axis further to the left, i.e. become profitable faster.

The first one shows the MRR development of several customer cohorts over the cohorts' lifetime:

Each of the green lines represents a customer cohort. The x-axis shows the "lifetime month", so the dot at the end of the line at the bottom right, for example, represents the MRR of the January 2013 customer cohort (all customers who converted in January 2013) in their 9th month after converting.

Each of the green lines represents a customer cohort. The x-axis shows the "lifetime month", so the dot at the end of the line at the bottom right, for example, represents the MRR of the January 2013 customer cohort (all customers who converted in January 2013) in their 9th month after converting.

Here are some of the things that you can see in this chart:

The second chart is based on exactly the same data but shows MRR for calendar months as opposed to cohort lifetime months, and it uses a slightly different visualization:

One of the things you can see here is the contribution of older cohorts to your current MRR (something to keep in mind if you're considering a price increase and are thinking about the impact of grandfathering):

The third chart shows cumulated revenues minus CACs for different customer cohorts, i.e. it shows how much revenues a customer cohort has generated less the costs that it took to acquire the cohort:

The purpose of this one is to show if you're getting better or worse with respect to one of the most important SaaS metrics: The CAC payback time, i.e. the time it takes until a customer becomes profitable. Note that for simplicity reasons the chart is based on revenues. If you use it in real life, it should be based on gross profits, i.e. revenues minus CoGS.

What you can see here is that the first cohorts cross the x-axis (a.k.a. become profitable) around the 6th lifetime month, whereas newer cohorts are crossing or can be expected to cross the x-axis further to the left, i.e. become profitable faster.

If you want to take a closer look, here's the latest version of the Excel template, which includes the new charts. Or even better, download it and pay with a tweet! :)

Friday, March 14, 2014

Cohort Analysis: A (practical) Q&A [Guest Post]

My colleague Nicolas wrote a great guide with tips and tricks on how to do cohort analyses which I'd like to share with the readers of this blog. Thanks, Nicolas, for allowing me to guest publish it here. Without further ado, here it is!

At Point Nine

we believe that the only way to get a real sense of user retention and

customer lifetime is doing a proper cohort analysis. Much has been said

and written about them and Christoph has a published a great template and guide on the topic if the concept is new to you.

With this Q&A I want to focus on some of the more practical questions that might arise when you are actually implementing a cohort analysis for your startup. After close to two years of working with SaaS companies and doing numerous of these analysis I have learned that in most cases there is no perfect step-by-step procedure. But although you will always have to do some customisation for a cohort analysis to perfectly fit your business, there are a handful of questions and pitfalls that I have seen over again and again and want to share so that you can avoid them.

Now let's get into it!

Q: Which users should I include in the base number of the cohort?

There are two parts to the answer as it depends on what you want to measure. If you want to find out your overall user retention and have a free plan, then you should include all signups of a specific month.

However if you are trying to calculate your customer lifetime value, you should only look at the number of paid conversions. I only count an account as a paid one when the user has or will be charged for a period. So if you offer a 30-day free trial for example, wait to see if the user converts into a paying plan before you include him in the cohort. This way the numbers won't be biased with users that actually never paid for your service.

If possible without too much effort, you should also try to eliminate all 'buddy plans' that you have given to friends, your team or investors. If they are not paying, they are not representative for the real cohorts.

Q: How do I treat churn within the first / base month?

There are different approaches here, but in my view taking churn within the first month into account is the most accurate representation of reality. That means that in your first month the retention could be less than 100%, if people cancel their paid subscription within that month. It would look something like this:

I do this because I don't want the analysis to exaggerate churn in the second month and understate it in the first / base month. After all the reasons for churning in the first 1-4 weeks could be very different than after 5-8 weeks.

Q: Should I treat team and individual accounts differently?

If you are at a very early stage or sell mostly (90%+) individual plans it is probably sufficient to mix them all in the same analysis. But when team plans make up a significant part of your paid accounts, or your product has a very different user experience when a whole team uses it, you should probably look at both type of accounts separately.

Findings could include that team accounts are a lot more active, churn less and see a lower drop-off in the first month than individual plans. Or not. :)

Q: What about annual vs. monthly plans?

Again, if you are focusing on how active your users are over their lifetime it is OK to mix both plans. If you just want to see how many of the people that signed up still come back after X months, no need to split hairs.

If you are however focused on churn, you should only look at paid accounts that could have churned in that month. This is one of the 9 Worst Practices in SaaS Metrics and means that you should exclude all annual plans that are not expiring in the respective month. Including these in the denominator would otherwise skew churn numbers.

Q: Now that I have it, what can I take away from it?

The two most obvious take-aways are depicted in this (KISSmetrics) retention grid. Note that this is a most likely an analysis for a mobile app and the numbers for your SaaS solution should be significantly higher:

Moving horizontally you can see how the retention of a cohort decreases over the users lifetime. Interesting here is where the highest drop-offs occur and whether the numbers stabilise after a few months.

Vertically, you can (ideally) see how the retention of your cohorts change over the product lifetime. Assuming you are not twiddling your thumbs while catching up with House of Cards or sipping Mai Tai’s at the beach once your product launches, you should see an improvement in user retention with younger cohorts as the product improves. If this is not the case, you should consider whether the hypotheses or features you are working on are the right focus.

Most importantly though, this data will be the basis to give you a sense for your customer lifetime value (CLTV). If you take the weighed retention data for the 6th or ideally 12th month and extrapolate it, you will get an approximation for the average lifetime of your customers. Multiplying this with the average revenue per account (ARPA) or respective plan that you are looking at (e.g individual / team) it will give you your CLTV. This number is really the quint essence of the cohort analysis, as it gives you an idea about how profitable your business model is (=how much more money are you making with than what you are paying to acquire him). Subsequently it will also tell you the highest price you can spend on customer acquisition to grow profitably. It is important to note here that although super valuable, especially in the early stages of a startup this number will always be an estimation and most likely not 100% accurate. So keep in mind to continually track and fine-tune your CLTV calculations.

And one last thing: If you have accounted only for paid subscriptions as defined at the first question above, then the base rates of each month will also give you the most accurate number for paid customer growth and subsequently MRR growth. Two charts you will want to have at hand when talking to investors.

Q: Is that it?

For this post, yup! If you want to learn more about cohort analysis or SaaS Metrics, I would strongly suggest to check out Christoph’s and David Skok’s blog. And in case you have any questions on the above or something is unclear, feel free to ask away in the comments or send me a mail and I will do my best to answer you (or forward the hard questions to Christoph). ;)

Like this post? Make sure you add Nicolas' blog to your reading list.

- - - - - - - - - -

With this Q&A I want to focus on some of the more practical questions that might arise when you are actually implementing a cohort analysis for your startup. After close to two years of working with SaaS companies and doing numerous of these analysis I have learned that in most cases there is no perfect step-by-step procedure. But although you will always have to do some customisation for a cohort analysis to perfectly fit your business, there are a handful of questions and pitfalls that I have seen over again and again and want to share so that you can avoid them.

Now let's get into it!

Q: Which users should I include in the base number of the cohort?

There are two parts to the answer as it depends on what you want to measure. If you want to find out your overall user retention and have a free plan, then you should include all signups of a specific month.

However if you are trying to calculate your customer lifetime value, you should only look at the number of paid conversions. I only count an account as a paid one when the user has or will be charged for a period. So if you offer a 30-day free trial for example, wait to see if the user converts into a paying plan before you include him in the cohort. This way the numbers won't be biased with users that actually never paid for your service.

If possible without too much effort, you should also try to eliminate all 'buddy plans' that you have given to friends, your team or investors. If they are not paying, they are not representative for the real cohorts.

Q: How do I treat churn within the first / base month?

There are different approaches here, but in my view taking churn within the first month into account is the most accurate representation of reality. That means that in your first month the retention could be less than 100%, if people cancel their paid subscription within that month. It would look something like this:

I do this because I don't want the analysis to exaggerate churn in the second month and understate it in the first / base month. After all the reasons for churning in the first 1-4 weeks could be very different than after 5-8 weeks.

Q: Should I treat team and individual accounts differently?

If you are at a very early stage or sell mostly (90%+) individual plans it is probably sufficient to mix them all in the same analysis. But when team plans make up a significant part of your paid accounts, or your product has a very different user experience when a whole team uses it, you should probably look at both type of accounts separately.

Findings could include that team accounts are a lot more active, churn less and see a lower drop-off in the first month than individual plans. Or not. :)

Q: What about annual vs. monthly plans?

Again, if you are focusing on how active your users are over their lifetime it is OK to mix both plans. If you just want to see how many of the people that signed up still come back after X months, no need to split hairs.

If you are however focused on churn, you should only look at paid accounts that could have churned in that month. This is one of the 9 Worst Practices in SaaS Metrics and means that you should exclude all annual plans that are not expiring in the respective month. Including these in the denominator would otherwise skew churn numbers.

Q: Now that I have it, what can I take away from it?

The two most obvious take-aways are depicted in this (KISSmetrics) retention grid. Note that this is a most likely an analysis for a mobile app and the numbers for your SaaS solution should be significantly higher:

|

| (click for larger version) |

Moving horizontally you can see how the retention of a cohort decreases over the users lifetime. Interesting here is where the highest drop-offs occur and whether the numbers stabilise after a few months.

Vertically, you can (ideally) see how the retention of your cohorts change over the product lifetime. Assuming you are not twiddling your thumbs while catching up with House of Cards or sipping Mai Tai’s at the beach once your product launches, you should see an improvement in user retention with younger cohorts as the product improves. If this is not the case, you should consider whether the hypotheses or features you are working on are the right focus.

Most importantly though, this data will be the basis to give you a sense for your customer lifetime value (CLTV). If you take the weighed retention data for the 6th or ideally 12th month and extrapolate it, you will get an approximation for the average lifetime of your customers. Multiplying this with the average revenue per account (ARPA) or respective plan that you are looking at (e.g individual / team) it will give you your CLTV. This number is really the quint essence of the cohort analysis, as it gives you an idea about how profitable your business model is (=how much more money are you making with than what you are paying to acquire him). Subsequently it will also tell you the highest price you can spend on customer acquisition to grow profitably. It is important to note here that although super valuable, especially in the early stages of a startup this number will always be an estimation and most likely not 100% accurate. So keep in mind to continually track and fine-tune your CLTV calculations.

And one last thing: If you have accounted only for paid subscriptions as defined at the first question above, then the base rates of each month will also give you the most accurate number for paid customer growth and subsequently MRR growth. Two charts you will want to have at hand when talking to investors.

Q: Is that it?

For this post, yup! If you want to learn more about cohort analysis or SaaS Metrics, I would strongly suggest to check out Christoph’s and David Skok’s blog. And in case you have any questions on the above or something is unclear, feel free to ask away in the comments or send me a mail and I will do my best to answer you (or forward the hard questions to Christoph). ;)

- - - - - - - - - -

Like this post? Make sure you add Nicolas' blog to your reading list.

Monday, February 24, 2014

Four (more) things we look for in SaaS startups

More than two years ago I wrote about what we look for in early-stage SaaS startups. Since then we've looked at hundreds of SaaS startups and have gained additional insights through the work that we've been doing with the SaaS startups that we have invested in. Therefore I thought it would be time for a follow-on post with some additional thoughts.

In the original post I focused primarily on early metrics as an indicator of product/market fit and of a favorable CAC/CLTV ratio in the future. Today I want to put more focus on factors that kick in a little later in the lifecycle of a SaaS company – aspects that have an impact on a company's ability to scale customer acquisition, increase ARPA and create lock-in. In other words, factors that can make the difference between a "good" and a "great" business.

Note that none of these factors is a must-have for building a successful SaaS company. For each one of them you'll probably find some great counterexamples. The point is that all other things being equal, these characteristics increase the odds of creating a big SaaS success:

1. High search volume combined with limited SEM/SEO competition

Search volume on Google is a good indicator of the awareness for the problem that you're solving. You may have a fantastic solution for a big problem, but if no one is looking for it, marketing it will be much harder. It means you'll have to spend more effort on educating the market and that you may not have a lot of low-hanging fruits on the customer acquisition front.

Related to search volume is of course competition for the relevant keywords, both with respect to SEM/PPC and SEO. If there's lots of competition for your keywords, PPC advertising might be prohibitively expensive and SEO will be much harder.

If, in contrast, there's high search volume and limited competition this not only indicates demand for your product, a gap in the market and potential to acquire customers via SEO/SEM. It also means that you have an opportunity to establish yourself as the thought leader in your space by doing great content marketing.

2. "Land and expand" and "bottom up" customer acquisition

Selling to big enterprises is tempting because one big enterprise deal can be worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. But it's also tough: Sales cycles are long, you need to convince various different stakeholders, there are special requirements for the product and you have to do multiple meetings to get the deal. Anyone who's done or tried it knows what I mean. Conversely, selling to SMBs is much easier, but the value of each customer is obviously a lot lower as well.

A "land and expand" or "bottom up" customer acquisition strategy has the potential to give you the best of both worlds. There are different variations of this strategy, but the idea is always that a single user or a small team of people inside a company starts using your product, making the initial sale easy (if any "selling" is involved at all). Over time, more and more people inside the company use it, and eventually you can sell an enterprise account to the entire company.

Perhaps the most famous example of a successful bottom up adoption is enterprise social network Yammer. Within the first two years after launch, the company's freemium distribution model attracted users from 80% of the Fortune 500 companies and got Yammer into more than 90,000 customers. According to this Mashable article, 15% of these companies subsequently upgraded to a paid plan.

If you want to follow in Yammer's footsteps (or just copy some pages from their playbook) here are some of the things you should keep in mind:

3. Virality

It's very rare for B2B SaaS applications to get really viral, i.e. have a viral coefficient of over 1. However, even though your SaaS product will never get Hotmail/Skype/Instagram/Snapchat-like growth, any level of virality is valuable because it means you're augmenting your paid user acquisitions with free users.

There are two primary ways in which a SaaS application can be viral:

a) "Sharing"

A use case which involves communication, collaboration, file sharing or the like with external parties. Examples include project management software like Basecamp (where e.g. an agency invites a client to a Basecamp project), e-signing solutions like EchoSign (where the person who is asked to sign learns about EchoSign during the process) or file sharing providers like Dropbox (you got the idea). The more affinity there is between your target group and their "collaborators", the better it is for you, since it means a higher "invite to signup" conversion rate.

b) "Publishing"

A use case where your customers use your software to create something which gets published on the Web. Examples: Shopify, SquareSpace, MailChimp or our portfolio company Typeform. Another example is Zendesk's feedback tab. The signup conversion rate is much lower in this case, but it can be offset if your product gets exposed to large numbers of people.

4. Economic moat

In the first couple of years you shouldn't worry too much about your long-term competitive advantages. Oftentimes execution is everything. Working harder than your competition, innovating faster and just doing everything a little bit better goes a long way.

Having said that, the best and most profitable companies in the world are those which manage to create wide moats around them – sustainable competitive advantages that allow them to keep market share and profit margins in spite of aggressive competitors. The best examples for wide economic moat are patents (think pharma) and natural monopolies (think eBay).

These two examples aren't very relevant for SaaS companies and there is no simple silver bullet for creating sustainable competitive advantage, but there are a couple of factors which can create moat around a SaaS business:

Perhaps the most famous example of a successful bottom up adoption is enterprise social network Yammer. Within the first two years after launch, the company's freemium distribution model attracted users from 80% of the Fortune 500 companies and got Yammer into more than 90,000 customers. According to this Mashable article, 15% of these companies subsequently upgraded to a paid plan.

If you want to follow in Yammer's footsteps (or just copy some pages from their playbook) here are some of the things you should keep in mind:

- Since you want to sign up users with little to no sales efforts you need a great marketing website and frictionless onboarding.

- Your product needs to provide value for a small number of users inside a company but even larger value if more people use it.

- Your pricing needs to be highly differentiated – make your product cheap or even free for a small number of users to maximize distribution and make money out of bigger accounts.

- Once you want to sell bigger team accounts or enterprise accounts you need to provide the functionalities required by bigger companies (a sophisticated role/permission system, SLAs, audit logs, etc.) while still keeping the product easy to onboard and use.

3. Virality

It's very rare for B2B SaaS applications to get really viral, i.e. have a viral coefficient of over 1. However, even though your SaaS product will never get Hotmail/Skype/Instagram/Snapchat-like growth, any level of virality is valuable because it means you're augmenting your paid user acquisitions with free users.

There are two primary ways in which a SaaS application can be viral:

a) "Sharing"

A use case which involves communication, collaboration, file sharing or the like with external parties. Examples include project management software like Basecamp (where e.g. an agency invites a client to a Basecamp project), e-signing solutions like EchoSign (where the person who is asked to sign learns about EchoSign during the process) or file sharing providers like Dropbox (you got the idea). The more affinity there is between your target group and their "collaborators", the better it is for you, since it means a higher "invite to signup" conversion rate.

b) "Publishing"

A use case where your customers use your software to create something which gets published on the Web. Examples: Shopify, SquareSpace, MailChimp or our portfolio company Typeform. Another example is Zendesk's feedback tab. The signup conversion rate is much lower in this case, but it can be offset if your product gets exposed to large numbers of people.

You can't force it if there's no sensible "sharing" or "publishing" use case for your product, but you should think about it carefully. If sharing or publishing doesn't make sense for you, you can still get some virality in other ways:

- Employee fluctuation: If you have a product that is used by lots of employees inside a company, try to make everyone an ambassador of your software who will suggest using your product in future jobs.

- Referral programs: FreeAgent's user-to-user referral scheme is a good example.

- Incentives along the lines of "get XYZ for a tweet", where users can e.g. unlock features or remove limitations by inviting people to your product.

4. Economic moat

In the first couple of years you shouldn't worry too much about your long-term competitive advantages. Oftentimes execution is everything. Working harder than your competition, innovating faster and just doing everything a little bit better goes a long way.

Having said that, the best and most profitable companies in the world are those which manage to create wide moats around them – sustainable competitive advantages that allow them to keep market share and profit margins in spite of aggressive competitors. The best examples for wide economic moat are patents (think pharma) and natural monopolies (think eBay).

These two examples aren't very relevant for SaaS companies and there is no simple silver bullet for creating sustainable competitive advantage, but there are a couple of factors which can create moat around a SaaS business:

- A platform. The best example is the Force.com platform. The large number of applications that integrate with Salesforce.com make Salesforce.com the most comprehensive CRM solution on the market and give the company a huge competitive edge. This is a classic example of a virtuous circle: More customers attract more developers which in turn attract more customers. When a platform has reached a certain size, it's very hard for competitors to attack you.

- Distribution channels: If you have thousands of partners who have been trained to sell your software and make a lot of money doing it, this can be another very valuable asset. Admittedly the role of VARs and other distribution partners is typically lower in SaaS than it is in traditional enterprise software, and the best example of an extremely valuable VAR channel is probably SAP.

- Lock-in: A great product with a fantastic user experience alone can create significant lock-in. But different types of SaaS products have different levels of lock-in. The more people inside a company use your product, the more business partners interact with the software and the deeper the product is integrated into a company's core businesses processes, the higher are the switching costs.

- Network effects: Great examples include Freshbook's billing network and MailChimp's eMail Genome Project. What these two examples have in common is that (at least in theory) every users makes the product more valuable for all other users.

- Big data: If you have tens of thousands of customers, the massive amounts of data created by your customer base might allow you to draw insights which you can then give back to your customers. Zendesk's benchmarking reports come to mind as an example.

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Measuring your SaaS success

I recently participated in Marco Montemagno's SuperSummit and gave a webinar about the topic "Measuring your SaaS success". Thanks, Marco, for inviting me!

Below are the slides of my talk. Since some of the slides aren't self-explanatory I've added some notes, see the yellow bubbles. If you want to dive in deeper, check out this post, which the talk was based on.

Below are the slides of my talk. Since some of the slides aren't self-explanatory I've added some notes, see the yellow bubbles. If you want to dive in deeper, check out this post, which the talk was based on.

Saturday, February 08, 2014

Contactually + MailChimp = yummy

Some time ago I wrote that we at Point Nine love to eat our own dog food. That is, we run Point Nine almost exclusively on Cloud apps. We're also heavy users of Zendesk, Mention, Geckoboard and other products from our own portfolio companies.

Another great example is Contactually. At its core, Contactually is a relationship management platform for salespeople and service providers in relationship-based businesses. The combination of two killer features – an address book that updates itself and a very smart system for so-called "follow-up reminders" – allows Contactually users to stay top of mind with all of their important contacts, which can have a huge positive impact on their business.

One really really nice thing which Contactually does for us is that it continuously adds subscribers to our (in)famous newsletter – almost automatically. Here's how it works.

1) By scanning my email accounts, the software automatically adds all new people who I'm exchanging a message with as contacts. You only have to connect your email accounts once, Contactually does the rest.

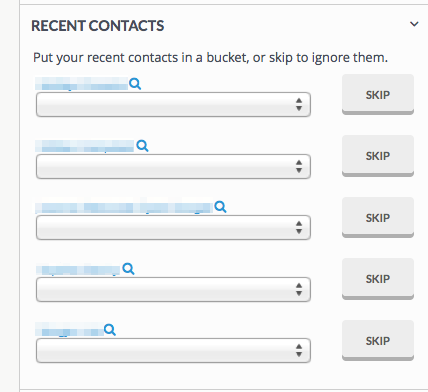

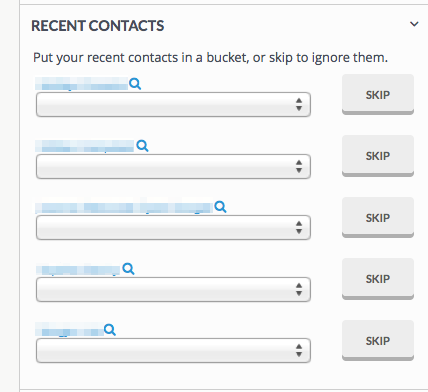

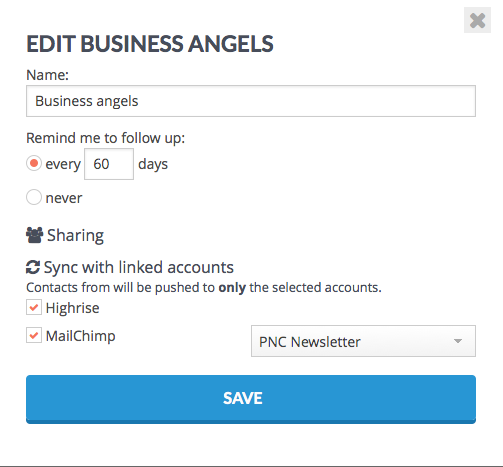

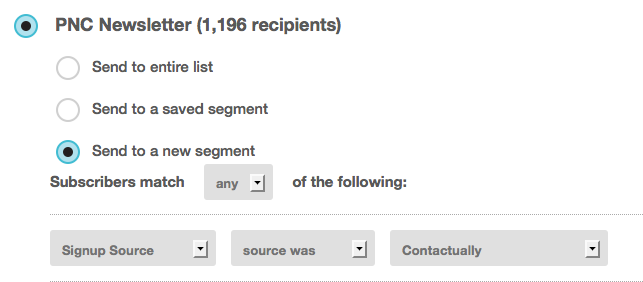

2) Every two weeks or so I put the new contacts into one of my "buckets":

This takes just one click per contact (and you can also do it from your mobile).

3) Then the magic starts. If I've added a contact to a bucket which is set to be synchronized with MailChimp, the contact will be pushed to our newsletter subscription list in MailChimp.

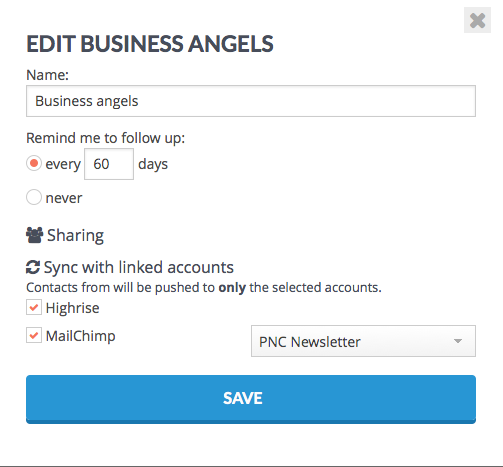

Here's how the bucket settings look like for these buckets:

If I don't want want to add the contact to our newsletter I just use a different bucket, one which is not set up for synchronization with MailChimp.

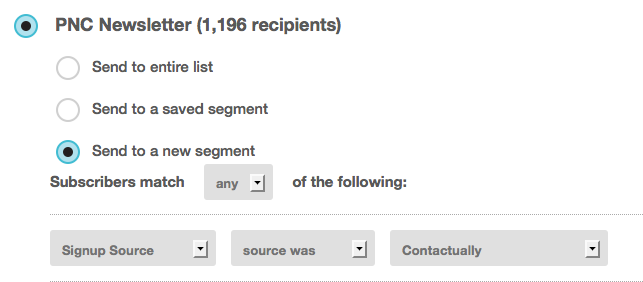

4) As soon as the new contact is pushed to MailChimp, the contact receives this email:

This is done using MailChimp's auto-responder feature:

That's it!

When we started this experiment we were of course wondering if it's too aggressive to automatically subscribe people to our newsletter. We came to the conclusion that it's OK if we're selective (i.e. only add people who we think are interested in news from us), have a fun confirmation email (see above) and have a one-click unsubscribe link. So far, we didn't receive a single complaint and very few people have unsubscribed, so it looks like it's working.

Another great example is Contactually. At its core, Contactually is a relationship management platform for salespeople and service providers in relationship-based businesses. The combination of two killer features – an address book that updates itself and a very smart system for so-called "follow-up reminders" – allows Contactually users to stay top of mind with all of their important contacts, which can have a huge positive impact on their business.

One really really nice thing which Contactually does for us is that it continuously adds subscribers to our (in)famous newsletter – almost automatically. Here's how it works.

1) By scanning my email accounts, the software automatically adds all new people who I'm exchanging a message with as contacts. You only have to connect your email accounts once, Contactually does the rest.

2) Every two weeks or so I put the new contacts into one of my "buckets":

This takes just one click per contact (and you can also do it from your mobile).

3) Then the magic starts. If I've added a contact to a bucket which is set to be synchronized with MailChimp, the contact will be pushed to our newsletter subscription list in MailChimp.

Here's how the bucket settings look like for these buckets:

If I don't want want to add the contact to our newsletter I just use a different bucket, one which is not set up for synchronization with MailChimp.

4) As soon as the new contact is pushed to MailChimp, the contact receives this email:

This is done using MailChimp's auto-responder feature:

That's it!

When we started this experiment we were of course wondering if it's too aggressive to automatically subscribe people to our newsletter. We came to the conclusion that it's OK if we're selective (i.e. only add people who we think are interested in news from us), have a fun confirmation email (see above) and have a one-click unsubscribe link. So far, we didn't receive a single complaint and very few people have unsubscribed, so it looks like it's working.

Friday, January 17, 2014

We ♥ vanity metrics ;-)

Who ever said only startups love vanity metrics? Here's our revenge for all those misleading stats that we have to muddle through almost on a daily basis when startups pitch us!

Yesterday I saw this post on the blog of Karlin Ventures. In response to a tweet by Paul Graham which was highlighted in Danielle Morrill's excellent Mattermark Daily newsletter, the guys at Karlin Ventures revealed the "days since last contact" numbers for their portfolio.

Here are the numbers for the 26 active companies in our current fund, Point Nine Capital II:

As written in Karlin Ventures' blog post, frequent communication is by no means a guarantee for helpfulness. Sometimes companies are in a phase in which the best thing an investor can do is to shut up and let the founders do their jobs. More often than not, though, I feel that a very close relationship and between founders and investors is a good sign. So – take a look at the stats above but don't read too much into them. :)

Friday, January 03, 2014

6 things SaaS founders should keep in mind in 2014

First of all, a Happy New Year to all readers of this blog. I hope you've had a great start into the new year, and I wish you a happy, healthy and prosperous (and of course SaaSy) 2014.

I've done a bit of reflection on what I've learned in the last couple of months. Here are six things that I think SaaS founders should keep in mind in 2014. This is obviously not meant as a definite or comprehensive list by any means. Rather, it's a synopsis of some of the things that keep me up at night these days.

1) Have the right mix of paranoia and patience

In the spirit of Andy Grove you need to be paranoid about becoming and staying the #1 player in your market. For a variety of reasons, most SaaS markets have "winner takes most" characteristics, so you have to do everything you can to dominate your market. But since we're still in the early days of Cloud adoption and since it usually takes 5-10 years to build a large SaaS company, you also need lots of patience. Gail Goodman of Constant Contact reminded me of that in this excellent talk.

2) Work on your weaknesses until they become your strengths

At the outset, almost every SaaS founder team that we talk to is either very strong on the product/tech side or on the sales/marketing side, but rarely on both sides. It's like a team DNA, and it's hard for a product-driven team to become excellent at sales and vice versa. At the same time, you have to be great at both product/tech and sales/marketing in order to succeed, so you should do everything you can to work on your weak side. This usually means a combination of a) learning really fast and going out of your comfort zone and b) hiring senior people with complementary skills and experiences. I'm not saying that you shouldn't leverage your strengths, but I know you're going to do that anyway. :) Doing what you love to do and what you're good at is comparably easy. Fixing your weaknesses is the tougher part.

3) Have a plan for 2014

Become clear on what you want to achieve in 2014 and what this means for your product roadmap, your marketing plan and your financial plan. Define company-wide OKRs as well as quarterly OKRs for each employee. It sounds like a no-brainer, but my guess is that most startups will benefit from going through a more structured OKR exercise. More about this in my recent post about OKRs.

4) Prioritize "mobile"

Mobile is eating the world. 'Nuff said.

If you don't offer your customers a fantastic experience on smartphones and tablets (which usually means native apps that leverage the unique capabilities of the device or the mobile usage scenario) you're at risk of getting disrupted by a mobile-first startup, faster than you can disrupt the incumbents of your industry.

5) Don't optimize for the edge cases

One thing I've noticed is that many startup founders are trying too hard to make everyone happy, which leads them to optimize pricing, sales tactics and maybe even product design for a small vocal minority of users. When I discuss e.g. lifecycle email marketing and pricing with SaaS founders I like to say:

The temptation to please every user is understandable but it doesn't mean it's the right thing to do. The pricing expectation of your users, for example, will probably follow some kind of bell curve. If you optimize for users on the far edges you're leaving a lot of money on the table in the much bigger middle area of the curve.

6) Raise money when you can, not when you need it

It's a pretty good time for SaaS startups to raise money. If you have the possibility to raise a meaningful amount of money at a good valuation, you should seriously consider it even if you don't necessarily need the money right away. First of all, it's usually unclear what "need" really means. Enough to get to break even? Enough to get to the next round of funding? Enough to win the market? More cash almost always means de-risking and an opportunity to accelerate. I venture to say that if you don't know what to do with an additional couple of million dollars that shows a lack of imagination. Secondly, I don't want to send a "R.I.P. Good Times" message, but currently the times are pretty good and no one knows what will happen in the next one or two years. Thirdly, just because you raise money doesn't mean you have to spend it imprudently, and most SaaS founders who I know are not at risk of failing due to premature scaling because frugality is part of their DNA.

What do you think about these six themes? Which additional ones do you think SaaS founders should pay attention to in 2014?

I've done a bit of reflection on what I've learned in the last couple of months. Here are six things that I think SaaS founders should keep in mind in 2014. This is obviously not meant as a definite or comprehensive list by any means. Rather, it's a synopsis of some of the things that keep me up at night these days.

1) Have the right mix of paranoia and patience

In the spirit of Andy Grove you need to be paranoid about becoming and staying the #1 player in your market. For a variety of reasons, most SaaS markets have "winner takes most" characteristics, so you have to do everything you can to dominate your market. But since we're still in the early days of Cloud adoption and since it usually takes 5-10 years to build a large SaaS company, you also need lots of patience. Gail Goodman of Constant Contact reminded me of that in this excellent talk.

2) Work on your weaknesses until they become your strengths

At the outset, almost every SaaS founder team that we talk to is either very strong on the product/tech side or on the sales/marketing side, but rarely on both sides. It's like a team DNA, and it's hard for a product-driven team to become excellent at sales and vice versa. At the same time, you have to be great at both product/tech and sales/marketing in order to succeed, so you should do everything you can to work on your weak side. This usually means a combination of a) learning really fast and going out of your comfort zone and b) hiring senior people with complementary skills and experiences. I'm not saying that you shouldn't leverage your strengths, but I know you're going to do that anyway. :) Doing what you love to do and what you're good at is comparably easy. Fixing your weaknesses is the tougher part.

3) Have a plan for 2014

Become clear on what you want to achieve in 2014 and what this means for your product roadmap, your marketing plan and your financial plan. Define company-wide OKRs as well as quarterly OKRs for each employee. It sounds like a no-brainer, but my guess is that most startups will benefit from going through a more structured OKR exercise. More about this in my recent post about OKRs.

4) Prioritize "mobile"

Mobile is eating the world. 'Nuff said.

If you don't offer your customers a fantastic experience on smartphones and tablets (which usually means native apps that leverage the unique capabilities of the device or the mobile usage scenario) you're at risk of getting disrupted by a mobile-first startup, faster than you can disrupt the incumbents of your industry.

5) Don't optimize for the edge cases

One thing I've noticed is that many startup founders are trying too hard to make everyone happy, which leads them to optimize pricing, sales tactics and maybe even product design for a small vocal minority of users. When I discuss e.g. lifecycle email marketing and pricing with SaaS founders I like to say:

"If no one is complaining about your prices, you're most likely too cheap"Similarly, if one user requests a new feature or a change in the product that's no reason to do it, unless you think it makes sense for a large part of your target group.

"If no one is calling your emails 'spam', maybe you're not sending enough emails"

The temptation to please every user is understandable but it doesn't mean it's the right thing to do. The pricing expectation of your users, for example, will probably follow some kind of bell curve. If you optimize for users on the far edges you're leaving a lot of money on the table in the much bigger middle area of the curve.

6) Raise money when you can, not when you need it

It's a pretty good time for SaaS startups to raise money. If you have the possibility to raise a meaningful amount of money at a good valuation, you should seriously consider it even if you don't necessarily need the money right away. First of all, it's usually unclear what "need" really means. Enough to get to break even? Enough to get to the next round of funding? Enough to win the market? More cash almost always means de-risking and an opportunity to accelerate. I venture to say that if you don't know what to do with an additional couple of million dollars that shows a lack of imagination. Secondly, I don't want to send a "R.I.P. Good Times" message, but currently the times are pretty good and no one knows what will happen in the next one or two years. Thirdly, just because you raise money doesn't mean you have to spend it imprudently, and most SaaS founders who I know are not at risk of failing due to premature scaling because frugality is part of their DNA.

What do you think about these six themes? Which additional ones do you think SaaS founders should pay attention to in 2014?

Friday, December 20, 2013

A KPI dashboard for early-stage SaaS startups – new and improved!

[Update 01/17/2015: There's a new company called ChartMogul (which we invested in) which makes it easy to get a real-time dashboard similar to the template below. Check it out!]

[Note: This post first appeared as a guest post on the blog of Totango. In case you don't know Totango, it is a powerful analytics product which gives online services the information they need to increase user engagement, conversion and retention. If you're a SaaS company you should check it out. Thanks to Guy Nirpaz and his team for publishing my post, which I am republishing here.]

In talking to a pretty large number of SaaS entrepreneurs in the last few years I've observed that there's a considerable amount of uncertainty around metrics: Which KPIs are the most important ones, what's the right way to calculate churn, CACs, MRR and other key metrics, how can I estimate customer lifetime value – these and other questions come up all the time, and the answers aren’t always obvious.

I've tried to address some of these questions in a couple of blog posts:

I also put together a template which I thought SaaS startups could find useful and which also makes it easier for us as a VC to communicate what KPIs we're looking for when we talk to SaaS entrepreneurs. Needless to say a template can only be a starting point, as every SaaS startup is different and needs to build its own, customized dashboard. Nonetheless it seems like the template, first published in April of this year, struck a chord with many SaaS founders and investors: The blog post got more than 60,000 page views (which I assume is quite a lot for a niche topic on a VC blog, at least if you’re not Fred Wilson :-) ) and I get requests for the Excel file every day.

In the meantime I’ve put some more work into the dashboard. You can download it here. (And if you like it, tweet it!)

Here’s how the charts look like with some sample data in it:

The main improvement of this version is that it now includes different pricing tiers and annual plans. This makes the spreadsheet considerably larger, but I feel it's necessary if you have multiple pricing tiers and contract lengths, and you can collapse a lot of the rows to get a concise view of the top KPIs.

I hope you find it useful! If you have any questions, comments or suggestions, please feel free to email me at christoph@pointninecap.com.

[Note: This post first appeared as a guest post on the blog of Totango. In case you don't know Totango, it is a powerful analytics product which gives online services the information they need to increase user engagement, conversion and retention. If you're a SaaS company you should check it out. Thanks to Guy Nirpaz and his team for publishing my post, which I am republishing here.]

In talking to a pretty large number of SaaS entrepreneurs in the last few years I've observed that there's a considerable amount of uncertainty around metrics: Which KPIs are the most important ones, what's the right way to calculate churn, CACs, MRR and other key metrics, how can I estimate customer lifetime value – these and other questions come up all the time, and the answers aren’t always obvious.

I've tried to address some of these questions in a couple of blog posts:

- 9 Worst Practices in SaaS Metrics

- Excel template for cohort analyses in SaaS

- The 8th DO for SaaS startups - Stay on top of your KPIs

I also put together a template which I thought SaaS startups could find useful and which also makes it easier for us as a VC to communicate what KPIs we're looking for when we talk to SaaS entrepreneurs. Needless to say a template can only be a starting point, as every SaaS startup is different and needs to build its own, customized dashboard. Nonetheless it seems like the template, first published in April of this year, struck a chord with many SaaS founders and investors: The blog post got more than 60,000 page views (which I assume is quite a lot for a niche topic on a VC blog, at least if you’re not Fred Wilson :-) ) and I get requests for the Excel file every day.

In the meantime I’ve put some more work into the dashboard. You can download it here. (And if you like it, tweet it!)

Here’s how the charts look like with some sample data in it:

|

| Click for a larger version |

The main improvement of this version is that it now includes different pricing tiers and annual plans. This makes the spreadsheet considerably larger, but I feel it's necessary if you have multiple pricing tiers and contract lengths, and you can collapse a lot of the rows to get a concise view of the top KPIs.

I hope you find it useful! If you have any questions, comments or suggestions, please feel free to email me at christoph@pointninecap.com.

Sunday, December 15, 2013

OKRs – objectives and key results

Last night I returned from a 2-day offsite with the Point Nine team (in Schlepzig, of all places). Our (small) full-time team more than doubled in the last six months, and this was the first time for all of us to spend some time together away from the daily bustle. We had a long list of topics that we wanted to discuss, ranging from investment theses to portfolio companies and to a number of projects that we're working on.

I wanted to kick off things with a session about our OKRs (objective and key results), and we had scheduled two hours for this agenda item. If you haven't heard about OKRs before, it's a methodology invented by Intel and popularized by John Doerr, the famous VC who invested in Netscape, Amazon and Google. The idea is (simply put) that a company needs to have clear objectives and that every department, team and person in a company needs to have objectives – and a set of key results for hitting those objectives – which are aligned with the company-wide OKRs.

We ended up spending the entire first day and some more time of the second day on this topic. This is particularly funny because I wasn't even sure if it's worth talking about our OKRs since I was wondering if they aren't obvious anyway.

Now, to be precise we didn't spend ten hours talking about our high-level long-term objectives. At a high level our goals are pretty obvious and I've written about them here. But diving in deeper and deeper brought us from one question to the next question, and by the time we were finished with the OKR session we've covered most of the topics which we had planned to discuss in other sessions. So on the one hand we completely screwed up the schedule that we had put together, on the other hand we covered most of the stuff that we wanted to get done in the end.

After this experience I am now even more convinced than before that every startup should use OKRs or a similar methodology to ensure that everyone in the company is on the same page and that there are clear and measurable goals. Scott Allison, founder & CEO of Teamly, wrote a great summary of the benefits:

But isn't this a no-brainer, don't all companies have a plan for the company as well as targets for most employees? Yes and no. All bigger company presumably have a budget and plan in place which is aligned with the company's objectives, but my guess is that what's often missing is linking that high-level plan to every employee's targets and communicating it throughout the entire organization. I'm pretty sure that if you randomly picked 100 employees of any Fortune 5000 company and asked them about the objectives of their companies you'd get lots of different answers. And in a fast-growing startup which doubles headcount every year and where each individual employee can have a much bigger impact than in a large enterprise, it's even more important that everyone is on the same page.

If you want to learn how Google (where John Doerr helped introduce OKRs) sets goals, watch this video from Google Venture's startup lab.

I wanted to kick off things with a session about our OKRs (objective and key results), and we had scheduled two hours for this agenda item. If you haven't heard about OKRs before, it's a methodology invented by Intel and popularized by John Doerr, the famous VC who invested in Netscape, Amazon and Google. The idea is (simply put) that a company needs to have clear objectives and that every department, team and person in a company needs to have objectives – and a set of key results for hitting those objectives – which are aligned with the company-wide OKRs.

We ended up spending the entire first day and some more time of the second day on this topic. This is particularly funny because I wasn't even sure if it's worth talking about our OKRs since I was wondering if they aren't obvious anyway.

Now, to be precise we didn't spend ten hours talking about our high-level long-term objectives. At a high level our goals are pretty obvious and I've written about them here. But diving in deeper and deeper brought us from one question to the next question, and by the time we were finished with the OKR session we've covered most of the topics which we had planned to discuss in other sessions. So on the one hand we completely screwed up the schedule that we had put together, on the other hand we covered most of the stuff that we wanted to get done in the end.

After this experience I am now even more convinced than before that every startup should use OKRs or a similar methodology to ensure that everyone in the company is on the same page and that there are clear and measurable goals. Scott Allison, founder & CEO of Teamly, wrote a great summary of the benefits:

- It disciplines thinking (the major goals will surface)

- Communicates accurately (lets everyone know what is important)

- Establishes indicators for measuring progress (shows how far along we are)

- Focuses effort (keeps organization in step with each other)

But isn't this a no-brainer, don't all companies have a plan for the company as well as targets for most employees? Yes and no. All bigger company presumably have a budget and plan in place which is aligned with the company's objectives, but my guess is that what's often missing is linking that high-level plan to every employee's targets and communicating it throughout the entire organization. I'm pretty sure that if you randomly picked 100 employees of any Fortune 5000 company and asked them about the objectives of their companies you'd get lots of different answers. And in a fast-growing startup which doubles headcount every year and where each individual employee can have a much bigger impact than in a large enterprise, it's even more important that everyone is on the same page.

If you want to learn how Google (where John Doerr helped introduce OKRs) sets goals, watch this video from Google Venture's startup lab.

Saturday, November 30, 2013

The 8th DO for SaaS startups - Stay on top of your KPIs

“What gets measured gets done” – it

seems like the source of this quote, often attributed to management

expert Peter Drucker, isn’t certain, but its meaning is clear and very

relevant for every SaaS founder. If you want to make sure that you make

best use of your scarce resources, you need to have a clear

understanding of your objectives and the KPIs that measure your progress

towards those objectives.

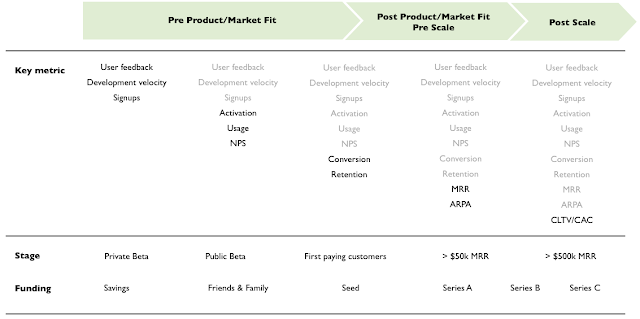

Depending on the stage that you’re in you’ll want to focus on different metrics. I’ve tried to illustrate this in the following diagram:

As you can see, I segmented the company lifecycle into three major phases: pre product/market fit, post product/market fit but pre-scale, and post-scale (being fully aware that there is no distinct definition of “product/market fit” and “scale” and that the transition from one phase to the next one is a gradual one). At the bottom I noted what these phases usually mean in terms of the stage of your product and company and which funding level it typically corresponds with. Note that the x-axis is not a true-to-scale representation of time elapsed. For a true-to-scale representation I would have to add much more space between the Series A and the Series B and between the Series B and the Series C.

The key message of the chart is that in the beginning you can focus on a small set of metrics, but as time goes by and you’re making progress you need to add additional KPIs to your cockpit.

Let’s have a closer look at each of the three phases.

Pre product/market fit

I’ve written about it before in my posts about sales and unscalable hacks: In the very beginning, when you’re in the process of finishing the first version of your product and trying to get the first customers, you shouldn’t worry too much about metrics. Firstly there just aren’t many metrics to keep an eye on yet. Secondly you should be obsessively focused on getting to product/market fit (Marc Andreessen’s words), and that means you should spend your time talking to customers and developing the product.

That said, the following metrics are relevant in the pre product/market fit phase:

Once you let potential customers try your product, the real fun begins. At that point, you should track signups and some indicators for activation and usage, which, for obvious reasons, are precursors to your ultimate goal, paying customers. What the right indicators for activation are depends on the type of your product. It could be a profile completion and the setup of a customized pipeline in case of a CRM application, the installation of a tracking snippet for a Web analytics product or… you get the idea. Similarly, usage metrics are highly specific to your application, so think about what the right events and parameters are in your particular case and make sure that you instrument your application accordingly. If your solution is a little more enterprisey and you’re working with a higher-touch sales model you may also want to track qualified leads along with trial signups.

In order to succeed you need happy customers who do free marketing for you, otherwise customer acquisition will always be an uphill battle. Therefore you should also consider regular Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys. If you’re looking for the best survey tool, I have a tip for you.

Post product/market fit, pre scale

As you’re slowly but surely getting to product/market fit and starting to get the first paying customers (yay!), your trial-to-paid conversion rate becomes one of the most vital metrics. It’s hard to give you a benchmark, since your conversion rate not only depends on the quality of your product and the onboarding experience but also on many other things such as leads quality, pricing and many other factors. With that caveat in mind, the typical range that we’re seeing is between 5% and 25%.

Equally important is your retention, usually tracked by measuring churn (the inverse of retention), since your CLTV (customer lifetime value) is a direct function of how much you charge your customers and how long they stay on board. As a very rough rule of thumb you should try to get your churn rate to 1.5-3% per month.

Make sure to track churn not only on an account basis but also on an MRR basis. Your MRR-based churn rate will hopefully be significantly lower than your account-based churn rate, since smaller customers tend to have a higher churn rate and because your loyal customers will hopefully pay you more and more over time. Also, make sure that you avoid SaaS Metrics Worst Practice #8, mixing up monthly and yearly plans. Finally, if you want to get a good estimate of your customer lifetime, take a look at retention on a cohort basis.

If you don’t have a KPI dashboard yet that gives you an at-a-glance look at your key metrics, now is the time to build one. Here’s a template that I’ve created, along with some additional notes.

As you’re moving on, arguably the most important metric becomes MRR, and specifically net new MRR that you’re adding each month. Net new MRR is calculated using this simple formula:

Post scale

When you’ve reached a certain level of success, say you’re at around $500k MRR, the biggest challenge (besides growing a bigger organization and mastering all kinds of growing pains of course) is to find ways to profitably acquire customers at a much higher scale. By this time you’ve picked all the low-hanging fruits, and you may have maxed out what you can reasonably spend on AdWords to buy traffic and leads.

Therefore you’ll have to focus on the relationship between your CLTV and your CACs (customer acquisition costs), your CLTV/CAC ratio, which measures the ROI on your sales and marketing investments. Another way to look at it is your CACs payback time, which tells you how many months of subscription revenue it takes to recoup customer acquisition costs. If I had to choose I’d pick this one, since CLTV is always an estimate which can be more or less accurate.

A few last points:

Depending on the stage that you’re in you’ll want to focus on different metrics. I’ve tried to illustrate this in the following diagram:

|

| (click image for larger version) |

As you can see, I segmented the company lifecycle into three major phases: pre product/market fit, post product/market fit but pre-scale, and post-scale (being fully aware that there is no distinct definition of “product/market fit” and “scale” and that the transition from one phase to the next one is a gradual one). At the bottom I noted what these phases usually mean in terms of the stage of your product and company and which funding level it typically corresponds with. Note that the x-axis is not a true-to-scale representation of time elapsed. For a true-to-scale representation I would have to add much more space between the Series A and the Series B and between the Series B and the Series C.

The key message of the chart is that in the beginning you can focus on a small set of metrics, but as time goes by and you’re making progress you need to add additional KPIs to your cockpit.

Let’s have a closer look at each of the three phases.

Pre product/market fit

I’ve written about it before in my posts about sales and unscalable hacks: In the very beginning, when you’re in the process of finishing the first version of your product and trying to get the first customers, you shouldn’t worry too much about metrics. Firstly there just aren’t many metrics to keep an eye on yet. Secondly you should be obsessively focused on getting to product/market fit (Marc Andreessen’s words), and that means you should spend your time talking to customers and developing the product.

That said, the following metrics are relevant in the pre product/market fit phase:

- User feedback: Most of the user feedback that you collect in this phase is qualitative rather than quantitative, but if you talk to a larger number of potential users you might also be able to add some quantitative elements. For example, you could ask users to rate your prototype and see if that rating goes up over time.

- Development velocity: I don’t know if (or how strictly) you should use a software development methodology like Scrum, which allows you to nicely visualize your development velocity, in the very early days, when you’re maybe just two developers – I would be very interested in your thoughts on that question. At any rate, however, I think it’s a good idea to break down your project into a larger number of smaller pieces, features or “story points” early on. This will help you in getting an understanding of your development speed, which later on will become more and more important.

- Waiting list signups: When you put up a landing page to collect email addresses for your waiting list, track how many signups you’re getting. Driving signups probably isn’t a key priority for you at this stage but it’s an indication of interest in your product and hey, you’ll still have some space on your Geckoboard which you can fill with a nice chart! :)

Once you let potential customers try your product, the real fun begins. At that point, you should track signups and some indicators for activation and usage, which, for obvious reasons, are precursors to your ultimate goal, paying customers. What the right indicators for activation are depends on the type of your product. It could be a profile completion and the setup of a customized pipeline in case of a CRM application, the installation of a tracking snippet for a Web analytics product or… you get the idea. Similarly, usage metrics are highly specific to your application, so think about what the right events and parameters are in your particular case and make sure that you instrument your application accordingly. If your solution is a little more enterprisey and you’re working with a higher-touch sales model you may also want to track qualified leads along with trial signups.

In order to succeed you need happy customers who do free marketing for you, otherwise customer acquisition will always be an uphill battle. Therefore you should also consider regular Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys. If you’re looking for the best survey tool, I have a tip for you.

Post product/market fit, pre scale

As you’re slowly but surely getting to product/market fit and starting to get the first paying customers (yay!), your trial-to-paid conversion rate becomes one of the most vital metrics. It’s hard to give you a benchmark, since your conversion rate not only depends on the quality of your product and the onboarding experience but also on many other things such as leads quality, pricing and many other factors. With that caveat in mind, the typical range that we’re seeing is between 5% and 25%.

Equally important is your retention, usually tracked by measuring churn (the inverse of retention), since your CLTV (customer lifetime value) is a direct function of how much you charge your customers and how long they stay on board. As a very rough rule of thumb you should try to get your churn rate to 1.5-3% per month.

Make sure to track churn not only on an account basis but also on an MRR basis. Your MRR-based churn rate will hopefully be significantly lower than your account-based churn rate, since smaller customers tend to have a higher churn rate and because your loyal customers will hopefully pay you more and more over time. Also, make sure that you avoid SaaS Metrics Worst Practice #8, mixing up monthly and yearly plans. Finally, if you want to get a good estimate of your customer lifetime, take a look at retention on a cohort basis.

If you don’t have a KPI dashboard yet that gives you an at-a-glance look at your key metrics, now is the time to build one. Here’s a template that I’ve created, along with some additional notes.

As you’re moving on, arguably the most important metric becomes MRR, and specifically net new MRR that you’re adding each month. Net new MRR is calculated using this simple formula:

Also

keep an eye on your ARPA (average revenue per account). It’s an

important metric at all times for obvious reasons, but as you’re nearing

the next phase it’s becoming even more important.

Post scale

When you’ve reached a certain level of success, say you’re at around $500k MRR, the biggest challenge (besides growing a bigger organization and mastering all kinds of growing pains of course) is to find ways to profitably acquire customers at a much higher scale. By this time you’ve picked all the low-hanging fruits, and you may have maxed out what you can reasonably spend on AdWords to buy traffic and leads.

Therefore you’ll have to focus on the relationship between your CLTV and your CACs (customer acquisition costs), your CLTV/CAC ratio, which measures the ROI on your sales and marketing investments. Another way to look at it is your CACs payback time, which tells you how many months of subscription revenue it takes to recoup customer acquisition costs. If I had to choose I’d pick this one, since CLTV is always an estimate which can be more or less accurate.

A few last points:

- Many startups struggle to get all these numbers together because different numbers are collected in different systems (e.g. Web analytics software, billing systems, self-made databases,...), which often leads to inconsistencies. I don’t have a simple and general advice for this issue, I might address it in another post.

- If you’re not sure which metrics to track, e.g. which events in your application, err on the side of tracking too much data even if you have no immediate use for it. You never know if it becomes useful in the future, and the costs for tracking large amounts of data are no longer very high nowadays.

- If you want to read more about SaaS metrics, I highly recommend David Skok’s blog and Joel York’s blog, as well as Jason M. Lemkin and Tomasz Tunguz.

That was it for the 8th DO for SaaS startups – questions, comments and suggestions are as always very welcome!

[Update 01/17/2015: There's a new company called ChartMogul (which we invested in) which makes it easy to get a real-time dashboard of your SaaS metrics. Check it out!]

[Update 01/17/2015: There's a new company called ChartMogul (which we invested in) which makes it easy to get a real-time dashboard of your SaaS metrics. Check it out!]

Monday, November 04, 2013

Impressions from the PNC SaaS Founder Meetup 2013

A little more than a week ago we did the second PNC SaaS Founder Meetup. Around the same time a year ago we organized our first SaaS Founder Meetup in San Francisco, this time we did it in Berlin.

Thanks to the incredible speakers and guests who came to the event it's been a truly amazing day, and I think all of the SaaS founders returned with a number of actionable insights which they can't wait to implement.

I was going to write a longer post about the event but decided to create some slides instead which hopefully capture a little bit of the great spirit of the meetup. Here you go:

If you want to view the presentation on SlideShare, here's the link.

Thanks to the incredible speakers and guests who came to the event it's been a truly amazing day, and I think all of the SaaS founders returned with a number of actionable insights which they can't wait to implement.

I was going to write a longer post about the event but decided to create some slides instead which hopefully capture a little bit of the great spirit of the meetup. Here you go:

If you want to view the presentation on SlideShare, here's the link.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Excel template for cohort analyses in SaaS

[Note: This post first appeared as a guest post on Andrew Chen's blog. Andrew is a writer and entrepreneur and has written a large number of must-read essays on topics such as viral marketing, growth hacking and monetization. He was kind enough to publish my post on his blog, and I am republishing it here.]

If you’re a long-time reader of my blog (or if you know me personally) you’ll know that cohort analyses are one of my favorite tools for getting a deeper understanding of a product’s usage. Cohort analyses are also essential if you operate a SaaS business and want to know how you’re doing in terms of churn, customer lifetime and customer lifetime value. I’ve blogged about it before and have included “Ignore your cohorts” in my “9 Worst Practices in SaaS Metrics” slides.

My feeling is that over the last 12 months the awareness for the importance of cohort analyses has grown among startup founders. One reason may be that thought leaders like David Skok have been writing about the topic, another reason are web analytic tools like MixPanel and KissMetrics that make it simple to create cohort analyses.

And yet, many founders are still having difficulties with cohort analyses, be it with the collection of the data or the interpretation of the results. With that in mind I wanted to create a simple cohort analysis template for early-stage SaaS startups.

You can download the Excel file here.

The idea is that you have to enter only a small amount of data and everything else is calculated automatically. Specifically, what you’ll have to type in (or import from a data source) is the basic cohort data: How many customers did you acquire in each month and how many of them were retained in each subsequent month. If you also want to see your churn on an MRR basis and get a sense for your CLTV, you’ll also have to enter the corresponding revenue numbers.

If you’re not sure how to read a cohort analysis, here’s a quick explanation:

Here are some brief notes on each of the arrays in the sheet:

A1: This is where you enter the raw data. Start with January 2013 and enter the number of new customers that you’ve acquired in that month. Then move to the right and enter how many of those January 2013 customers were still customers in February, March, April and so on. Then move on to the next row. If your data goes further back than January 2013, extend the table accordingly.

A2 and A3: A2 takes the data from A1 and shows it in “left-aligned mode”, making it easier to compare different cohorts. As you can see the columns have changed from specific months to “lifetime months”. A3 shows the number of churned customers as opposed to the number of retained customers. Both A2 and A3 aren’t particularly insightful to look at per se, but the data is necessary for the calculations in B1, B2 and B3.

B1: Shows the percentage of retained customers, making it easy to see how retention develops over time as well as to compare different cohorts with each other. What you’ll want to see is that younger cohorts are getting better than older cohorts.