With some delay I'd like to continue my little series:

3rd DO for SaaS startups

Create an awesome product

This one is a little tricky. Firstly because it feels like I'm just stating the obvious – who doesn't want to create an awesome product? Secondly because it's hard to offer a lot of useful advice in a blog post on a topic which shelves of books have been written about. But a series on the DOs for SaaS startups would be incomplete without at least one DO about the product I and will focus on a few aspects that I personally feel strongly about.

As mentioned

before, I'm going to assume that you want to build a modern SaaS solution for the

"Fortune 5,000,000". This most likely means that you won't have a field sales force and that you're going to use a low-touch online sales model instead. What implications does this have for your product?

The entire user experience – from the first time the user visits your site to the moment he signs up for a free trial, through the onboarding and the exploration of the product and further on – needs to be completely

frictionless. It should be designed with the same mindset that designers of online shops have, e.g. when they design a checkout process: Any little thing that doesn't work flawlessly, anything that may make the user doubt can kill a few conversion percentage points.

If your product is complex, and chances are that your product will have significant complexity at least from a new user's point of view, hide a big part of the complexity from the new user and give him or her a way to

gradually discover it. When you have the user's attention, you have to fight to keep it against a million possible distractions. Make the learning curve as smooth as possible and give the user as much gratification along the way as possible. The masters of this discipline are designers of games that teach the game to new users in many small steps, meticulously making sure that it never gets too difficult nor boring, giving the user lots of little gratifications along the way.

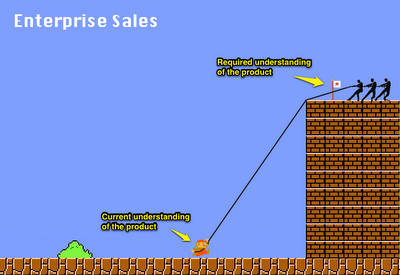

Speaking about games, I think this is how product discovery looked like in the old enterprise software world:

Poor Mario is faced with an insurmountable barrier, and it takes the vendor's sales and support team (those little guys on the right) to pull him up that mountain, which means lots of money and time spent on sales, setup and training – and a lot of time and reasons for Mario to give up before reaching the flag.

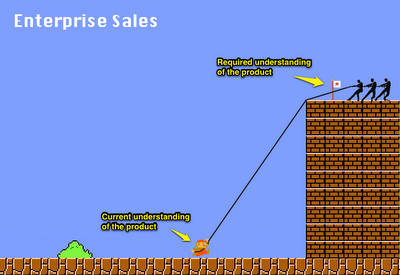

Contrast that with new world of self-service, low-touch sales SaaS:

The big barrier has been torn down, and the way to the required understanding of the product is paved with several "aha" moments (those little trampolines which help Mario jump to the next step). *

Online shops, games, instant gratification, gradual discovery – by now you can probably guess the bigger theme that I'm heading at: The

consumerization of enterprise software. The

consumerization of enterprise software means that the way enterprises buy software is changing. Keep that in mind – you're not developing a product for IT professionals (unless you

are offering a product to the IT team) who are super tech savvy and will make a choice based on a feature matrix. Your product will be used by marketing, sales, HR, support or finance people or founders or managers of small businesses – whatever the case may be – and your product must be easy enough to use so that a typical member of your target group can come to your site, start a trial and see the value of your product with little to no intervention from your company.

_________________________

* Thanks to

Roan Lavery of

FreeAgent, whose presentation at out recent

SaaS Founder Meetup was the inspiration for the images above.